Climbing Mount Hood

There’s nothing like it.

Standing on top of or even just high up on a mountain as grand and as beautiful as Mount Hood can be a truly amazing experience.

Climbing Oregon’s tallest peak, which an estimated 8,000 to 10,000 people attempt to do every year, can also be exhausting, unnerving, dangerous, and even deadly.

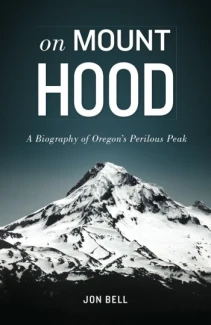

Two of my favorite chapters in On Mount Hood explore the world of climbing on Mount Hood. It’s a subject that has fascinated me since the day I first saw the mountain back in 1997.

Tonight, (March 29, 2012),Oregon Public Broadcasting’s show Oregon Field Guide takes its own look at climbing the mountain in an episode called “Mount Hood: Climbing Oregon’s Highest Peak.” It airs at 8:30 p.m. and again at 6:30 p.m. on Sunday, April 1. It will also be online in the not-too-distant future. Judging by these short videos here, it should be a great show for any and all fans of the mountain.

Camping lesson

The Mount Hood National Forest was host to one hell of a party a few weeks ago.

We’d pitched our tent in a favorite area out near the rushing Sandy River, a place we’ve spent many a night over the past few years. The specific spot that we usually favor was already taken when we rolled up, but no worries. There were a few other options nearby, and the one we landed in boasted a nice view of the mountain through the trees and more shade than the old faithful spot.

This place has been great to us ever since we stumbled on it a few years ago. Because it’s not a campground, but instead a handful of dispersed sites, it’s relatively free of the crowds that flock to the more developed areas. And though you don’t have to hike in to get to it, it’s got a measure of serenity and beauty that almost hints at wilderness. Plus, the river’s just a short jaunt away.

Once we had our camp on in the late afternoon hours, the cars started rolling by. First one. Then another. And another. A Jeep with four young guys in it. A pickup truck rumbling with bass. A little sedan that had no business on such a rough road weighted down with folks.

The party, in the site a couple down from us, kicked off as the first cars pulled up. A car door would slam, some loud greetings would exchange, and then the beverages would crack open. I know how it works. I’ve been to my fair share of those, especially back in the pre-21 days. This was one of those.

It raged throughout the night, as the sun set, the mountain faded, the stars shone. Loud laughter, obnoxious machismo, breaking glass. Because we were a few sites away — and because we remembered what we had been like at that age — it wasn’t so bad. Just different than our normal escapes up there. Louder, mainly. And surprisingly, we just about outlasted the rowdies. By the time we retired from our own quiet campfire, it was pretty close to silent throughout the woods.

The next morning, the same cars we’d watched roll in the night before rolled back out in the early morning sun. My five-year-old daughter and I took a walk down the dusty road to survey the damage. And that’s when I changed from a slightly annoyed but somewhat understanding neighbor into an incredibly disappointed and perturbed curmudgeon. There was trash along the road, broken glass in the bushes. A pair of pants with who knows what on them sat crumpled up under a tree. Toilet paper streamed from the manzanita, camping chairs lay broken and bent on the ground, and the last car to leave loaded up the fire pit with trash, set it ablaze and drove away.

It was not pretty.

It needed to be cleaned up. I didn’t want to do it, but I knew we’d probably be back up for another weekend sometime this summer. I also knew that the Forest Service had been tolerating these unregulated sites, but that they were beginning to rethink that approach. Posted on all the sites in the area, for the first time since we’d camped there three or four years ago, were some unfortunate signs.

After mulling it over at breakfast and not being able to leave it alone, my daughter and I grabbed some plastic bags, headed back over to the trashed site, and cleaned it up. Five garbage bags, two wrecked camping chairs and a couple bucks worth of returnables later, it looked hospitable again. Probably still needed a good rain before I’d pitch my tent there again, but it was on its way.

I’d like to think that when I was that age, I would have been a little more conscientious about the things I did and didn’t do, but to be honest, I’m not sure I would have. Back then, a lot of it was about having new fun and, sometimes, not holding onto any evidence. I understand that. But years later, my perspective has swung over to the other, more adult and responsible side; the side that cannot fathom how anyone could leave a campsite just a few hundred yards away from the Sandy River and with a lovely view of Mount Hood in such littered disarray.

Who knows how many more scenes like that the Forest Service will have to walk up on before they do actually close those beautiful sites to everyone. I consider myself lucky to have found a place like this, to be able to enjoy an escape like this.

It’s easy to take these places for granted. It’s best not to.

Another climbing anniversary

In recognition of the 11th ninth year since one of Mount Hood’s most memorable and tragic climbing accidents, which happened on May 30, 2002, I was going to offer up another short excerpt from On Mount Hood.

The passage would have come from a chapter I call Accident that looks at the tragedies that have unfolded on and around Mount Hood, from the very first time a climber met his maker on the mountain — it was a Portland grocer named Frederic Kirn, who in 1896 was swept off Cooper Spur by a rockslide — to a trio of climbers who tried to sneak in a climb up the Reid Glacier Headwall during a brief weather window in December 2009. In between, the chapter touches on everything from the Mount Hood Triangle and the OES tragedy to a freak accident in the volcanic vents high up on the mountain and a tragic slip that cost a married couple their lives. When the latter happened, I was a few hundred feet below the summit on my very first climb of Hood ever.

But the highlight of Accident, for me anyway, is a story about something that happened eleven nine years ago today. It involved several different climbing teams, a renowned Portland physician climber, a U.S. Air Force Pave Hawk helicopter, and a pararescue jumper named Andrew Canfield.

But rather than share an excerpt from the book here, I instead decided to embed an unbelievable video that captures a dramatic part of the story.

The rest is in the book.

Other mountain books

Though I’m biased toward one particular mountain and one particular book, the alpine canon is full of adventurous, inspiring, heartbreaking, and possibly even life-changing works. There are also a lot of lemons in there too. But in this post, we’ll focus on just a few of the better ones, a few of my favorites.

Art Davidson’s classic account of the first winter ascent of Denali.

Art Davidson’s classic account of the first winter ascent of Denali.

Another memorable recounting of a first, this one of the first successful climb of a treacherous wall on the Eiger in Switzerland known as the White Spider.

Another memorable recounting of a first, this one of the first successful climb of a treacherous wall on the Eiger in Switzerland known as the White Spider.

A must-read for anyone who wants to know anything and everything about Washington’s Mount Rainier.

A must-read for anyone who wants to know anything and everything about Washington’s Mount Rainier.

PRC number 4

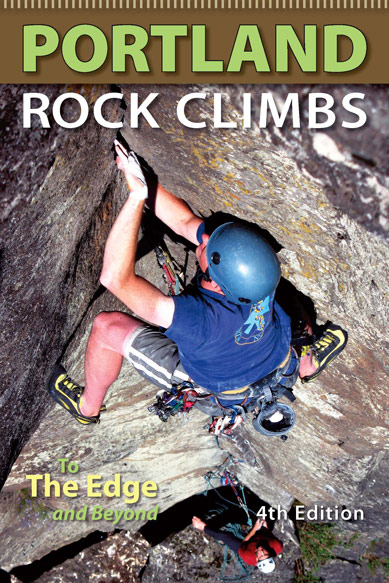

In addition to climbing on Mount Hood, there is also climbing to be done all around Mount Hood — and all around the greater Portland area. The best guidebook for all of that kind of climbing — from Bulo Point and French’s Dome to Rocky Butte and Beacon Rock — has long been Tim Olson’s Portland Rock Climbs.

My copy dates from 2001 and is nicely dog-eared and tattered from a good three- or -four-year stint of regular rock climbing back in the days before kiddos. These days, that book sits on the shelf more than I’d like, but it’s still there, and I still pull it out every now and then.

For those who are still able to hit the Portland-area rock hard, however, Olson has just released the 4th edition of Portland Rock Climbs.

Updated and revised, the new volume covers all the classic climbing spots around Portland, the Gorge and Mount Hood. The new version also includes information on places like Ozone out on the Washington side of the Gorge and also a little write-up of Beacon Rock giant Jim Opdycke by yours truly.

Pick up a copy at Tim’s web site or at one of the retail locations he’s got listed there.

25 years ago . . . the OES tragedy on Mount Hood

Today marks 25 years since the worst climbing accident in all Mount Hood history: Nine dead, seven of them high school students from the Oregon Episcopal School. They’d been part of a team climbing the mountain for OES’ annual Basecamp Wilderness Education Program. The weather turned hellish, they didn’t turn around, the climb fell apart. Searchers found three bodies two days later; six more the next day in a snow cave buried under five feet of snow, but also, miraculously, two survivors.

For a number of reasons, I didn’t dwell too deeply on the OES disaster in On Mount Hood. I did touch on it, of course, and I also wrote briefly about its legacy on Mount Hood 25 years later for Portland Monthly this month. The latter story included an interview with Rocky Henderson, a well-known search-and-rescue volunteer whose very first mission ever with Portland Mountain Rescue was the OES climb.

“It was so frustrating,” Henderson told me of the search efforts. “When the weather finally cleared, we thought, ‘OK, now we’re definitely going to find them.’ But we didn’t. By then, there were no clues as to where they were. They had been completely obliterated by the storm.”

Something about climbing accidents intrigues people, myself included. And Mount Hood has had its share of them. But even though I was 12 and living in Ohio when it happened, there’s something singular about the OES accident. The scale of it, the what-ifs, the age of the victims. It’s heartbreaking. I read The Mountain Never Cries, a book by Ann Holaday, mother of Giles Thompson, one of the two OES survivors. I read all of the stories in the Oregonian from during and after the accident, the People magazine story, the piece in Backpacker, and on and on.

It is a sad but incredible story. One worth remembering, always.